Today when I woke up, I found #talkpay trending on twitter. (Yes, what better way to enjoy your morning coffee than with a thousand astonishing tech salaries and 160-character comments?)

Where’d this come from? Well, Lauren Voswinkel wrote in ModelViewCulture that men and women could address salary inequity in the tech sector by sharing salary, experience, title, and location with the hashtag #talkpay. (Joseph Zumalt analyzed UIUC librarians similarly a few years back; check out his sweet Table 2.) Because skilled data scientists and software developers are in high demand and short supply, I bet #talkpay really can help underpaid devs better negotiate with their employers—and walk if the negotiations don’t work.

#talkpay for libraries?

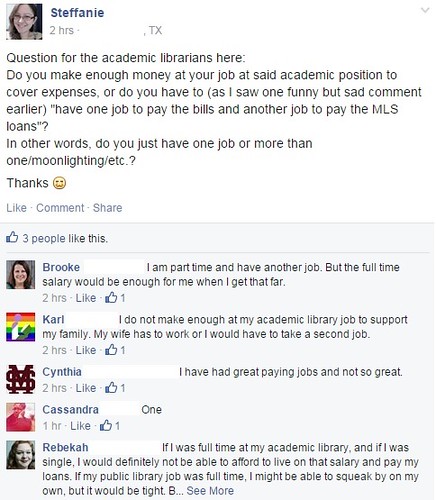

But what about us? In the past few years, I’ve watched librarians make repeated attempts to share salary data (and I’ve previously pulled median librarian incomes and IQR by state, here) and try to raise demand for our skills. But our market really differs in supply and demand, at least for now. Librarians are in a different place, even if we make the same info-sharing moves as our tech peers:

The problem? If many other applicants bring similar skills, experiences, and education as I do, then I’ve less room for negotiating. And given that some library schools put out 500+ new grads every year, one recent MLS grad often doesn’t have significant leverage compared with another (but not always. Tech/data skills and high-profile project experience help). Skilled web developers and data scientists masquerading as librarians are an exception—but that’s because they can more easily leave for tech if things don’t work in libraryland.

So how do we fix this as individuals?

First: develop extensive software development skills and data science skills. These add some leverage for you in the library market, but mostly if you’re willing to move industries when library negotiations don’t work out.

Then, ensure that you’re willing to move anywhere or into any industry. Again, this flexibility combined with unique skillsets gives you maximum leverage on the market. Moving was a key result from my survey of 385 recent MLS grads last November: nearly half of new librarians had to move states or cities for a job, and it may be harder to get a job if you can’t move.

Of course, I know these tips don’t work for many of us. Maybe we joined libraries because we’re more literary than techy. Or because we care about libraries. Maybe we have family and spousal needs that we actually care about.

We’re not all Economic Man, nor should we be.

How do we fix collective supply and demand?

And yet. If we really wanted all librarians to have rising salaries and opportunities, we would need to address macroeconomics. First, we’d need to address supply: develop a regulating body for our labor market, restrict entry into library schools, deal with the oversupply of existing recent MLS grads, make it hard to get in school and complete rigorous tech/conceptual/data courses, and/or cut off the flow of volunteers and part-timers by establishing licensure. That fixes supply… although I suspect we’re 50 years late for some of those measures.

But there’s still the issue of demand: the perception by those hiring that part-timers, temps, or volunteers are an adequate substitute. That a bookstore clerk and a librarian pretty much do the same job. That they don’t need more librarians. The frequency with which random strangers ask “do you think you’ll have a job in ten years? I mean, will libraries still be around?” suggests to me a need for strategic, grounded PR–PR that proves our unique value in terms that others value. Do we have that value? If not, we need to work on it.

In short, we’d all be better off if we were all able to walk–and if employers couldn’t replace our skillset when we did.

In other words, both the oversupply of librarians and the undersupply of demand for the skills that MLS grads advertise suggest that we won’t see changes in the market, unless we make substantial changes in the skillset and marketing of librarians to meet the top 2-3 most urgent needs of businesses, communities, and government leaders today.

(And yet… our admirable ethos of access for all and a focus on the marginalized can itself be in tension with the interests of the 1%. E.g. watch Lessig’s brilliant speech at ACRL. In a view from the top, the best data scientist, policy wonk, or educational specialist tends to be the clever but unquestioning one.)

Sí, se puede… but will we?

So let me suggest a set of tasks for the newly-elected president of the ALA (American Library Association):

1) Fix supply for librarians by:

- pushing library schools to stop admitting so many students

- ensure that those who graduate have few loans and are placed in full-time, related jobs

- and placing most existing graduates, retraining with tech skills if necessary

2) Then, bolster demand for librarians in the public, school, higher ed, and commercial sectors:

- By raising the bar for entry to library school (high GREs, coding skills, tech skills required, as at Berkeley’s iSchool).

- Market the hell out of our specialized, hard-to-get, and extremely sought-after skills

- Overall, police the market to ensure that librarians have unique and monetarily-valued skills that few can offer for the same price.

As Barack Obama advertised, Sí, se puede! It can be done.

But do we want to do it?