Everything is looted, spoiled, despoiled /

Death flickering his black wing, /

Anguish, hunger—then why this /

Lightness overlaying everything?

— Anna Akhmatova, trans. D. M. Thomas.

I went to Karaganda with my colleague Lia and her friend Grace this week. Grace is visiting from England for the week; “I’ve dragged her all over, except Astana,” Lia says to me, laughing as Grace snaps a few pictures of the Bayterek. “It’s not really fair.” This morning we meet outside the train station, crisp and bright, the morning sun slanting across the temirzholi and avtovokzal signs. Taxi, taxi, several standing men say, clutched in small circles around gray and blue vans.

“Myi troyom,” Lia announces to the clustered drivers, blustering up in a headscarf and leather jacket. High-heeled leather boots wrap her calves; she’s lived in Kazakhstan for several years and converses comfortably in Russian.

It’s a two-hour trip to Karaganda, a center for mining as well as the city nearest to the old Soviet gulags in Kazakhstan. To get there, we’re looking for three seats in a hired car, but they only have one or two places left – or five. But a hired car never leaves until it’s full; it’s important to time these things well. “2000 each,” a man offers for a large van, but it comes with at least a 15-minute wait. “Nyet, nyet” Lia shakes her head, “nada s’chas.” We need it now. I begin to speak in Kazakh; the driver knocks the price down to 1500 ($10) each for the two-hour drive.

But Lia’s not inclined to wait. She chases down another driver who asks for 2500 each and promises to leave right away. Young and taut, he wears a woolen cap and leather jacket. We agree. So driving down through Astana at high speed, we cut to the highways at the south edge of town; he thrums along the road to Karaganda. Weaving in and out of traffic, the driver cuts just between a truck and the oncoming truck, a rush of redbrown at our swerving side. Lia dozes peacefully with her jacket over her head: Grace and I sit stiffly and watch the traffic with wide eyes.

“It’s best to look away,” I murmur. Grace nervously faces the windshield from the middle seat, and looks for a seat belt, taking mine.

“We’ll make it there in two hours,” I add, “that’s the virtue of a car. But you don’t have to worry about dying on the road… that’s the virtue of a train.”

She smiles thinly. In front of us, a trendy girl in a checked scarf takes a video of the roadside on her iPhone, white headphones dangling from her ears.

As we hit the countryside, the autumn landscape flattens into wide plains of large-headed wild grains, except for small patches of “river,” narrow ponds tucked into dips in the land. Signs announce small towns 5km off the road. We dodge cars crossing into our lane on the ‘bad’ stretch of road. The space is immense.

Temirtau

As we approach Temirtau, the driver gets into an anger-match with another guy, necks tensing, hard stares from car to car. He stares down the road as they race around the soft-sided semi-trucks; one has signage in German and the other promises Good Food in English. Our boy pushes past the other car, driving at 140 km per hour until we’re well out of sight.

Temirtau’s name means “iron mountain” in Kazakh, and some 20-40 km before Karaganda we see it on the road, smokestacks rising above the low city. Gorod metallurgikov: a concrete sign announces the City of Metallurgy.

“The children live here,” Lia tells me. The rich children at our school? I’m surprised. “No, no, the parents have a house here, they own the factories,” she corrects me. We trade jelly-chocolate biscuits and Sprite.

Karaganda

As we arrive into Karaganda, a city of half a million people, a sign advertises the airport; a later driver tells us that they have international flights, as well as flights from local airlines like Air Astana (and the infamous SCAT airlines, which crashed outside of Almaty last year).

The afternoon light shines brightly as we are deposited by the unmarked taxis at the train station. Lia asks the price to Dolinka, the former administrative center of the Karaganda gulag.

“5000, one way,” an older man says. “5000, oi, too much,” Lia protests, her voice rising. “It’s far,” he insists. They settle on 8000 ($55) there and back, and he’ll wait for us while we tour the museum.

This driver, Dulat, wears a woolen vest under his jacket, and a small cap. Lia sits beside him. He tells us that he only speak Russian; 90% of people in Karaganda speak Russian. “It’s because of the Soviets,” he says. He had a Kazakh father and a Russian mother, and wants to know our ethnicity. Well, Lia’s English and I’m American.

“But it’s the same in America,” I add. “People with us are mixed too.” I mention Obama.

“Your Obama got elected and he’s not a real American,” Dulat says.

“His father’s African and his mother’s American. He’s real,” I say.

“But he wasn’t born there!” Dulat insists.

We burst out laughing. “Yes, he was born in Hawaii,” I say.

“Really,” he says, in jest or serious, “that’s why America killed that president in the middle east.”

Which one? I’m thinking: bin Laden, Hussein… “Hussein?”

“No, Qaddafi,” Dulat tells us. “He knew the secret, Obama’s secret about where he was born.”

Dolinka

20 km out from Karaganda is the small town of Dolinka, where low white buildings hide behind wooden fences, sporting peaked roofs and faded green trim. We later learn that these were the type of buildings that the young guards and workers lived in. A woman stands by the bus stop, waiting for a ride into town.

As we drive into the town, Dulat points out an enclosure of broad white walls, which hide a modern-day prison. Around the corner is the bright white museum, once the central administrative building of a prison camp stretching for 6500 square miles (1.7 million hectares, similar in size to all of Kuwait); it’s recently been remodeled. They’ve done weird things to advertise it like a night in the gulag (here).

Lia snaps pictures of a black dog on the marble steps; Grace intently captures the whole panorama of garden, fountain, facade. The museum is closed for lunch, so Dulat takes us to the town cafeteria, which offers cold chicken pre-plated with grains, small plates of salad, a pile of unwashed dishes. We order sweet creamy cakes, and cups of hot tea with a gray film hovering in them.

Over tea and cakes, Dulat asks our ages. Lia, Grace, and I are all single and over 25, old enough to be a kari kiz (old maid) in Kazakhstan.

“So why aren’t you married?” he says.

“I’m trying!” Lia responds. “I’m looking for one.”

Dulat promises her that there are more men in Karaganda than in Astana, what with all the mining. “So four to one?” Lia turns to me, doubtful. She says there are five times the women as men in Kazakhstan, and 10 to 1 in the capital city.

“Why so few men?” I ask. “Was it the Great War?” [WWII]

“Cancer. And alcoholism, and car accidents,” she responds. Knowing how young men drive, I believe it.

The Karlag Museum

When we come back, the tour has already started in Russian. “You’re late,” the guard accuses. “We don’t want the tour. We can’t speak Russian,” we tell him in Russian.

A girl is assigned to mind us, and watches Grace anxiously until she puts her camera away. We walk through rooms with neatly displayed photos, and scans of old prison documents. One group is ahead of us, but we’re mostly alone. The museum is well-designed, the best I’ve seen here, and I hope Kazakhstan will develop more such museums to cover other periods in their history.

[[Spoiler alert: take a trip to Karaganda yourself; the notes below are for my friends who will never get there or otherwise learn much about the gulags in Kazakhstan…]]

As we look at the small signs in three languages, we learn that the building was the old administrative center for the Karlag, as the work camp (Rus=”lager”) at Karaganda was called. The town of Dolinka was the administrative center for the dozen provinces that made up the camp, each with its own industries—cattle and sheep and horses, a pig farm, women forced to milk (“registration of the milk,” one picture reads, as women line up before an official with their large pails of milk). The male and female prisoners dug root vegetables, cabbages and melons, meeting quotas for each type of metallurgy, factory output, production of coal and grains and millet and wheat. Forced labor was a major contributor to the success of Soviet Russia: over 18 million people passed through the gulags, as Applebaum notes in her book; over one million came through Karlag as prisoners at some point; millions more were not imprisoned, but merely exiled to Kazakhstan.

Karaganda oblast always exceeded its quotas, at 117%, 134%, the sign boasts. But of course.

Famine

The first rooms tell of the famine, with enlarged pictures of bare boys with bloated bellies, men laid out to die in carts, beggars struggling for food. From 1932-1934 the famine was at its worst. It seems that after the Soviets took over the Kazakh provinces, they took herds and land for their own purposes. There were protests. Some Kazakhs killed their own animals to avoid having them seized. Hunger spread across the steppe, as Kindler covers so well here. (An elderly Kazakh woman named Nŭrziya tells her story here: it’s worth a read.) Over one million Kazakhs died; half the survivors fled to other lands.

And a few years later, the first shipment of Chechens arrived, 40 trains with cattle cars containing 25,000 people who were poured out onto the steppe with nothing in their hands. As the museum takes care to highlight, some Kazakhs helped them survive.

Men were shipped to Karlag to work; women were often shipped to separate camps, such as the Alzhir camp near Astana. In one year, the sign reads, 650 pregnant mothers were sent to the camps. Children came too, and died in large numbers, buried in their own separate cemetery. Imprisoned mothers could keep their children with them until the age of four, at which point they were sent to orphanages for ‘reeducation.’ A portrait shows boys and girls in a row waiting to be sent away. Mothers wrote letters pleading for their children’s care; the boys and girls were raised until the age of 15 and then sent out into the world to work.

After this introduction, the girl leads us into the basement. The rooms darken.

It’s all designed for emotional impact (the music is sad in every room except the one about women and children?). The stairwell walls are covered in a plaster of hands and fists, barbed wire twined into the hands. To our right, a room.

Go in, the guidegirl gestures.

We look in, and startle. A man, a real man, seems to be staring back at us. His eyes are wide and pale; we expect him to speak. The room a strong glow of red and brown, an isolation chamber with heavy metal doors.

We back away; the next room has a man in a pit, heavy metal grate above his folded body. The wax men look as though they would speak. In solitary confinement, the sign reads, prisoners were given 300 grams of bread per day plus a hot mug of water; every three days a reduced hot meal.

Other basement rooms contain replicas of a barracks with narrow wooded boards as bunkbeds; a kindly Kazakh waxman at the table with tin dishware. A library has a pastewood card catalog, drawers askew. An infirmary holds narrow metal beds, elderly waxwoman stretched out to sleep, her neck thrown back. Syringes rest in the cupboards, metal implements waiting beside puffed metal flasks.

In the science lab, a man has been brought in to work calculating crop gains among the vials and tubes. “At least they could do work they liked,” Lia says. The waxman seems intent on his work; Lia almost touches his shoulder as she looks over his notebook, below.

Then the interrogation room, with uniformed man at the desk and another clenching keys behind an empty seat. On the wall a photo: a handsome young officer with a cigarette in his lips. This is not a man you could reason with.

A room for photographing, where a prisoner sits, hands fallen into his lap. At the end of the hallway, a waxman faces a brick wall, hands behind his back and dark red wounds in the bricks around him.

“Were they shot here?” Lia asks.

“Not in the building,” the guidegirl says. “They were shot outside in the summer, but indoors in the winter.”

“Here?”

“No,” she shakes her head, “this was the administration building.”

“Did the prisoners ever come here?”

“Of course not,” she says, “they were elsewhere.”

Up to the highest floor again, lightness. A cove displays artwork by a prisoner named Pavel Rechenskii. The Holy Spirit of the Karlag, one reads, a kind ghost hovering over the camps. The path to hell, another is written.

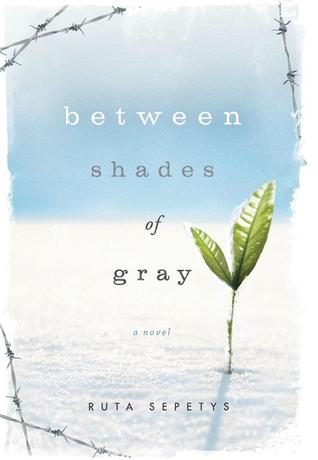

A cattle car has been tucked into one room, a scattering of suitcases by its side. Forty people were sent out in one railroad car, the size of a marshrutka van. It recalls the book Between Shades of Gray, about a Lithuanian girl sent with her family to Siberia, hovering between death and life in the far north. The author, Ruta Sepetys, interviewed survivors and the results are stunning, award-winning:

A chart on the wall shows the communities who were sent by Stalin to their exile: Germans, Chechens, Tatars, Koreans, Iranians. Families, writers, scientists, politicians: anyone a crazed dictator could find reason to fear. (Another book to read: Dancing Under the Red Star, about a young American named Margaret in the gulags. I find it striking how both Nŭrziya, above, and Margaret survived through faith, in Allah and God respectively.)

This imprisonment, this multiethnic exile, is the source of Kazakhstan’s proud interethnic harmony: 130 nations living together in one land.

Above, a broad room with quiet green walls and a fine wooden desk. By curtains fluttering at the window, a man stands. He looks out over the village, wax hands in the pockets of his untucked uniform. Commander, contemplating. A painting on the other wall shows generals laughing and working; displays in the first rooms showed pretty 1940s girls with their boyfriends, the workers who staffed the camps.

And a final room, brightly lit, gives us the easy narrative of modern Kazakhstan: the harmonious meetings of world religious leaders. Peace. Books. Productivity. Alga. Forward.

Minerals

Dulat takes us back to Karaganda, past the empty quarries cut into the ground. We cross the road to Aktas where gold has been found and will soon be mined. “It’s just lying in the ground right now,” he says, as if we could pick it up. There’s a factory with dark foothills of coal. Dulat tells us it’s good to be a miner.

“But it’s dark!” Lia protests.

“What do you mean?” Dulat says, looking at Lia. “It’s light, with electricity below ground, and also railroads.” We’re not sure what to believe.

Along the road, there’s a major factory owned by some Indian, one who bought all the coal mines in England. He now owns part of Kazakhstan, too. “Indians, Americans, Chinese, they all come and take,” Dulat says. Wealthy men own this land.

The Kazakh girls I know can’t decide if they’re proud of their mineral wealth, or aggrieved at the big men who carry it all away.

Karaganda

It’s a perfect fall day, and Karaganda appears a lovely city. I’d heard it was grim, an industrial city with pollution, heavy metals, cold dark winters. It may be true, but today the thin trees shine with the sun’s pale yellow, a boy and girl kiss beneath the statue of Soviet workers, and the fresh air lightens our lives. The shops at Tsum are stocked with glittering goods, and families duck in and out of Interfood for fried chicken pelmeni. It feels restful, inhabited. People seem happier here.

We have a coffee – this is how I tour the world – and walk back to the train station. Another man drives us back to Astana, but twenty minutes after leaving Karaganda, his phone rings. Ketip bara jatirmin, he says, you’re too late. I already left on the road to Astana. Tomorrow, yah, I’ll bring the refrigerator.

As we pull into Astana’s center, the bright moon reflects off the giant egg five stories tall that comprises the state archive. For a moment, light glances sharply from one particular panel. We look up, in surprise. There, light–then darkness. We could almost glimpse the lamp of a solitary historian, alone in his room, crafting the story of Kazakhstan late into the night.

How are you? I know that you are also in Astana, working in library. I just wanted to ask you if you could give me your mobile or call to mine, as I have proposal to you to participate in one TV project about forreigners who live in Astana.

Beautifully written! I visited my family in Karaganda this summer and we went to Karlag as well. My grandfather(s) were prisoners/workers there, because we are German. Well, it was nice to relive the experience. I was allowed to take photos there because my cousin knows the manager, if you’d like some then just let me know 🙂

Jutta, thanks for your lovely note and the offer of photos! So glad you got to visit the Karlag; it sounds especially meaningful for your family. I hope you found other places around Kazakhstan interesting as well.

Pingback: Gulag og erindring - Minerva

It is a crime against humanity that individuals, like me, who were born in a gulag have never been recognised or compensated for the hell we endured, the consequence of this have left, those of us who survived, with PTSD. Consequently being imprisoned with the labels invented by the quackery invented by psychiatry. In the name of humanity please recognise not only our existence but also compensate us for damage done, thank you.

Hello Michael. Might be able to help. Please get in touch with eml address.